GENERATIONS IN MY BODY: LAKSHMI MADHAVAN

August 08 - September 19 , 2024

A thread, a yarn,

a cloth… a skill, a livelihood, a community… a story, a history, a generation.

Lakshmi Madhavan

grew up watching her widowed grandmother wear a differently bordered kasavu mundu veshti all her life. Though the artist lived in

Mumbai, she was always aware of being an outsider in the city. Lakshmi rejected

her Malayali roots and felt alien to her own language and culture. When Lakshmi

lost her grandmother in 2021, she was desperate to find ways to reclaim her grandmother’s

memories. Language and food were a residue compared to Lakshmi’s strongest sensorial

memory – the whiff of her grandmother’s rice starched veshti. Holding onto this cord, the artist was plunged into a vortex from

which yards of creation, recognition, acceptance and generational histories

emerged for a future telling.

The roots of her grandmother’s veshti link back to the kasavu weavers’ community in Balaramapuram, Kerala. However, the kasavu weavers who are considered

traditional to Balaramapuram proudly trace their ancestry to the Shaliyar community that originated from Thirunelveli in Tamil Nadu. By placing their

livelihood outside of their belonging, the weavers’ bodies become functional

producers located within a geography that they do not identify with. For

Lakshmi, a quest to thread a family member’s history, cascaded into historic

pasts of communities, and generational beliefs that were entrenched in bodily

functions of caste, purpose and allowances of belonging.

The artist’s initial visits to the kasavu weavers’ community in Balaramapuram

were met with hostility. She was looked at as an outsider trying to come in to

disrupt their system. This was until Lakshmi met her master weaver, Jayan, who guided

her through the nuances of the community. He asked her one question: “What is the purpose of doing this?” “A

memory for my Ammamma (grandmother)”, was Lakshmi’s reply. He responded, “Your story is my story. After I die, they’ll shroud me with the last cloth

I have woven and all of these looms will go silent. Your grandmother carries

the same anxiety of you not continuing your journey with this land, your birth

land.” Jayan passed away shortly

after too, but his kasavu weavers became the artist’s link to open up worlds

that continue to exist well beyond memory keeping.

While Balaramapuram continues to

be the central space where Lakshmi creates works with the kasavu weavers, the experiences of working with them is a constant grounding process

through incidents, rituals, nuanced layers of acceptance and rejection, and reconstructing

new belief systems. It is in these focused and tightly knit, yet fragile communities

that a realisation of the layered worlds within a world came to exist.

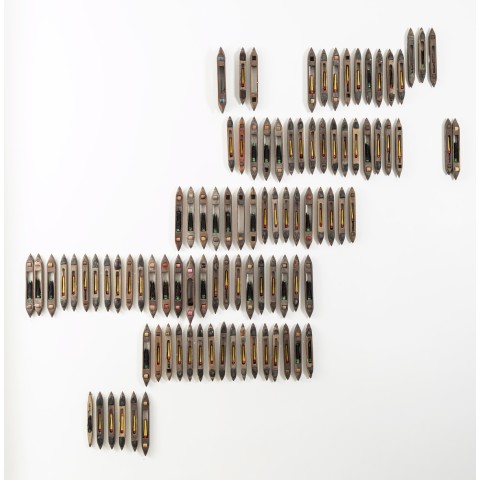

The exhibition seeds from an installation of ninety-six shuttles, the

age Lakshmi’s grandmother lived until. The bare shuttles wrapped with kasavu threads and hair (a carrier of genes) become the invisible loom that

spools out yarns of words and stories into the rest of the exhibition. A wooden

chest filled with rice water starches memories of Lakshmi’s grandmother, her

ancestral home, family gatherings and sounds of the past. These sounds spool

into the space and settle on the red laterite bricks sculptures that hark the

soil of Kerala to weigh down the bodies that create shadows across the room.

The shadows that sometimes fold onto the woven kasavu pieces are perhaps the

closest these bodies will come to draping the fabric, similar to the weavers

who laboriously weave this textile over months and sometimes, years, only to be

worn by another body belonging to another caste. Histories, caste systems and

memories tide through centuries in the weavers’ bodies as they do in ours.

There is a sudden realisation of being the other body. This othering occurs

when the body is assigned a name. The name associates it with a caste and colour

privilege. The caste determines how the body can don the kasavu that none of its weavers can ever wear.

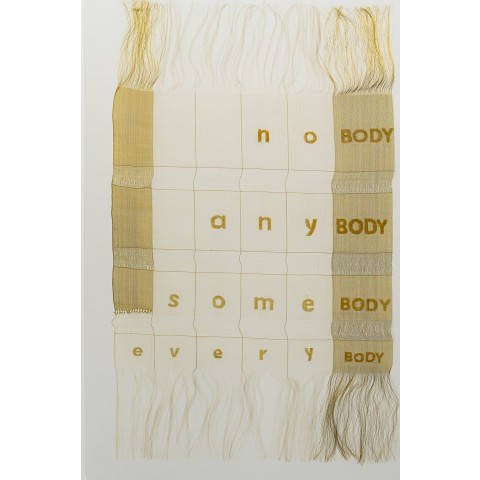

Within the kasavu fabrics that Lakshmi creates with her weavers, she

incorporates words that appear singular but weigh down the movement of time within

a narrative. Akin to a knot and the complexity of a switch from white to gold

thread on a loom, these woven words invite pauses and interventions for a

viewer’s body and story. The lightness of the fabric, barely sheer, elicits

wonder, beauty and snatches of joy at first. These are quickly shadowed by

reflections of fear, anger, and empathy. The errors that personalise a handloom

weave versus a machine weave become metaphors for the bodies that toil to carry

burdened truths of past generations. Sweat drops and silent shadows are the

only remnants that carry onward from the weavers’ bodies onto the wearers’

bodies. The cloth becomes a marker of commodification and an identification of

recognising the hierarchy of a body. But the body is no longer singular. The

body belongs to a weaver, who belongs to a community, similar to the wearer who

drapes the fabric on their body which decomposes and passes on within

generations to be worn by other bodies.

Text by Veeranganakumari Solanki