JEHANGIR SABAVALA: PILGRIM SOULS, SOARING SKIES, CRYSTALLINE SEAS

October 29 - December 10 , 2020

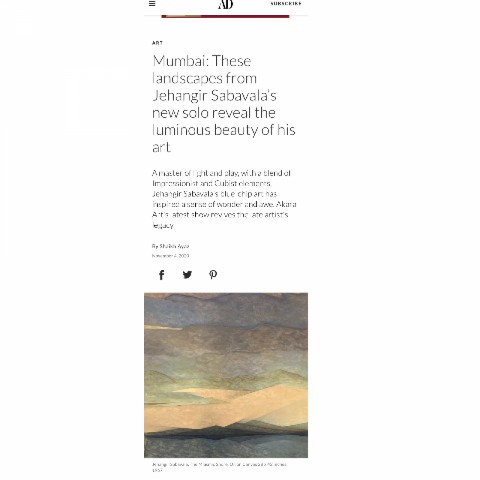

1.Jehangir Sabavala (1922-2011) was fascinated, all his life, by the mystery of light and the phenomenon of expanse. Light, which is all around us, can transform our surroundings radically without possessing a material presence. Its moods, varying with time of day and year, convey a gamut of emotional states from exhilaration to pensiveness to melancholia. Sabavala registered the play of light, whether the soft diffusion of a European morning or the sharp angularity of an Indian afternoon, through the micro-tones of his sophisticated palette. Expanses of all kinds delighted his spirit – in his visionary landscapes and seascapes, the shore stretches out to meet the tide, the sea surges out to the horizon, the skies form an illimitable dome above shoreline and snowline.

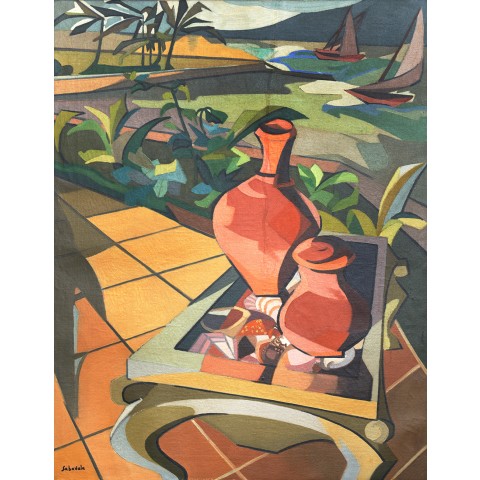

Sabavala was committed to the practice of oil painting – and later, to painting in acrylics – in the studio, and kept up a lifelong, unvarying schedule of regular working hours. This led some observers to compare him to a professional attending his office. On the other hand, Sabavala also delighted in plein air painting, setting up his palette in a piazza in Italy or on a beach in France, and rendering what he saw around him in vivid watercolour: the architecture of churches or public buildings, the cascade of houses in a valley, the relationship between built form, social life, and nature. ‘Portofino’ (1953) and ‘Santa Euphemia’ (1954) demonstrate this aspect of Sabavala’s practice.

More often, whether he was looking out at the spectacular theatre of clouds and waves across the Arabian Sea from his studio windows, or while on vacation in the Sahyadris or the Kumaon Himalayan foothills, he would transcribe and modulate what he saw in elegantly structured drawings. Each of these drawings was annotated with astonishingly detailed ‘colour notes’ in Sabavala’s notebooks: micro-tones of colours, whether yellow, grey, blue, or red, which were eventually graded into scales on his palette and veined into his paintings. There were, of course, transpositions: colours originally glimpsed in a cloud might migrate, in the finished painting, into water; tints observed on rooftops might come to rest in a pattern of leaves.

2.

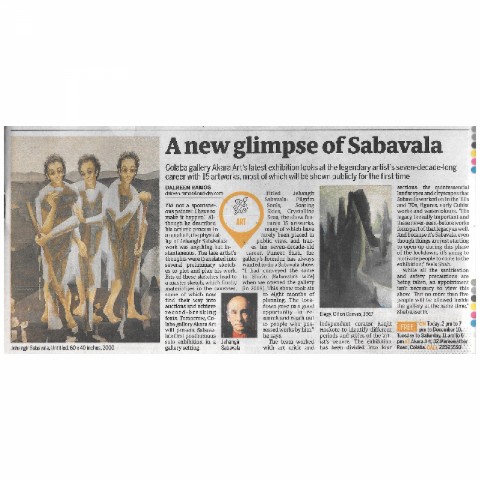

Jehangir Sabavala: Pilgrim Souls, Soaring Skies, Crystalline Seas is the first posthumous solo presentation of Sabavala’s work in a gallery context. It celebrates each phase of this magisterial artist’s seven-decade-long career through a thoughtful selection of memorable paintings, a number of which have rarely before been placed on public view.

Sabavala was one of the most distinguished members of India’s first generation of postcolonial artists. Born to the aristocratic Cowasji Jehangir Readymoney family in Bombay, as Mumbai was then known, he spent his childhood and early youth in India and Europe. Unlike many of his relatives, who were patrons of the arts – and collectors of art whose interests ranged from Chola bronzes to Rajput miniatures – he chose to be an artist. He was educated at Elphinstone College and the Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art, Bombay; the Heatherley School of Art, London; and at the Academie Andre Lhote, Paris. Between 1951, when he held his first exhibition at the Taj Mahal Hotel, Bombay, and 2008, when ‘Ricorso’, his last solo was held at the city’s Sakshi Gallery, Sabavala progressed with poise and elegance from one theme and formal preoccupation to the next. He engaged with the still life and the landscape, reimagining both through a post-Cubist lens. He evolved a distinctive visionary approach to the natural world, evoking veiled geographies of slopes and ridges, mysteriously clouded mountains, serene plains, and uncharted waters.

3.

Having lived in England and France during the latter half of the 1940s, Jehangir and Shirin Sabavala returned to a newly independent India after six years in the UK and France. Over the 1950s and early 1960s, Sabavala embraced his homeland through travel, sketches, and an immersion in the cultures of India’s various regions. During these decades, the Sabavalas would travel to Kerala and Rajasthan, to Madhya Pradesh, the Sahyadri Hills and along the course of the Tungabhadra River. Transiting from his Cubist training to a stylised vocabulary that was distinctively his own, the artist took up three objectives. First, to render the spirit and symbolic nature of place. Second, to edit and format his paintings in an aesthetically satisfying manner. And third, to communicate to his viewers the operatic sense of an identity negotiating with its ambience, expressing its findings in rich colour, exuberant motif, and innovative strategies of design. His success is evident in such accomplished paintings as ‘Sanchi’ (1960), where the Cubist framework of balancing pictorial tensions has been reshaped to serve the genius loci), and also in ‘Earthenware against the Sea’ (1952), ‘Sheaf of Corn’ (1964), and ‘Heraldic Birds’ (1965).

I shall dwell briefly on ‘Sanchi’ (1960) to draw attention to an unregarded aspect of Sabavala’s method. Given the personal testimony of authors such as myself – the artist’s biographer and friend of several decades – as well as the evidence of his notebooks, with their rigorous sketches and palette notations, it has usually been understood that Sabavala’s process took him invariably from sketch to painting. I suggest that ‘Sanchi’ bears witness to the photograph – taken on site, during the Sabavalas’ visit to the Buddhist heritage site near Bhopal, in Central India – as the point of departure. Consider how the landscape is treated here as a still life, its close-up frame pulled back to establish the stupa in mid-shot, while elements of foliage, closer to the eye, seem larger in scale than in real life. Evocations of fruit, stone, and leaf infuse this painting: our eyes are delighted by its chromatics of plum, puce, slate, chalk, lime, and viridian.

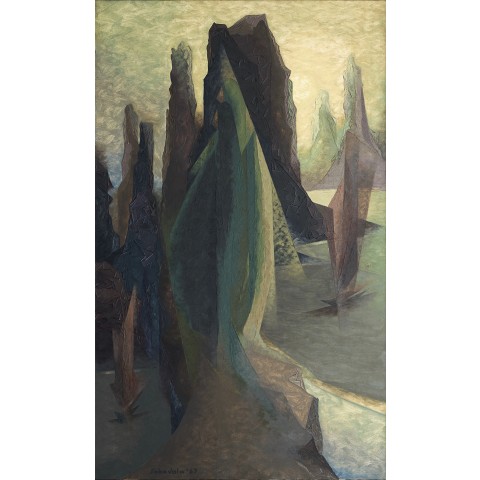

The early 1960s marked a turning point for Sabavala’s art, a pivot between his earlier phase of apprenticeship to the European genealogies of impressionism, expressionism, and cubism, and his later phase of individuation, when he evolved a recognisable personal style through which to articulate his specific painterly concerns. Between 1961 and 1964, he broke away from the suffocating formality of Synthetic Cubism, to which he had apprenticed himself at Andre Lhote’s academy in Paris. Departing from the impasto materiality of his earlier work, with its knife-edge lines, thick borders, and grand masses, he softened his paintings. In this enterprise, he took inspiration from the work of the German-American expressionist Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956).

Composing a statement in response to a questionnaire posed by the American art critic George Butcher in 1964, Sabavala wrote, in the spirit of a manifesto: “No longer am I satisfied with the juxtaposition of planes, the search for rare colour, the almost total denigration of the unpremeditated. It is the intangible which is now my goal. Space and light, and an element of mystery begin to permeate my canvases. Emotions seek a new release in what I hope will become a permanent synthesis of heart and mind.”

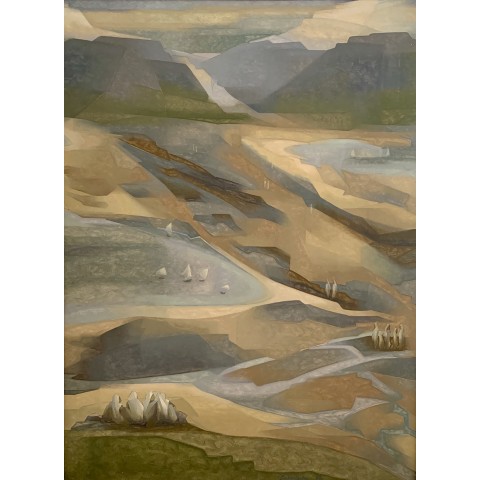

Accordingly, across the 1960s and 1970s, the presence of light – whether dawn’s radiance, sunlight diffused through mist, the afterglow of twilight, or the shadowed luminescence of night – became one of his key subjects. In paintings such as ‘Beached Boats’ (1962), ‘The Miasmic Shore’ (1967), ‘Elegy’ (1967), and ‘The Shadowed Strand’ (1977), Sabavala allowed light to permeate the canvas as tissues, as suffusions, to produce a mysterious shifting topography of translucent seas, opaque headlands, clouded plateaux, and free-floating atmospheric forms. His handling became freer, his emphasis shifted from the particular to the universal. Eventually, Sabavala’s ships and boats would become identified with that further shore which lies beyond our nautical charts, our mortal efforts. Moving towards the crystalline, his landscapes and seascapes began to approach the transcendent, the cosmic.

4.

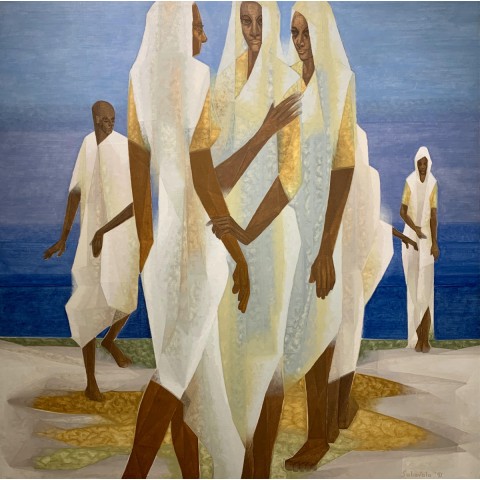

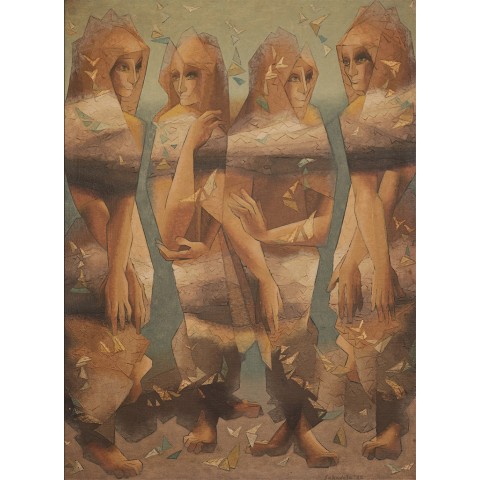

Over a period of nearly seven decades, Sabavala’s evocation of the human figure embraced a breath-taking diversity of types and temperaments, ranging from the earthly to the otherworldly. Through his expansive domains wander enigmatic figures: these are sometimes reduced to ephemeral details in the sublime vastness of nature; and at other times, they dominate their environment robustly as they continue on their journey towards unknown goals. Some of these figures may be pilgrims, others explorers, yet others villagers; given Sabavala’s preference for presence over likeness, they do not necessarily belong to a definite locale but draw on regional physiques and temperaments.

Reflecting on his own diasporic heritage as a Parsi, whose ancestry linked him to refugees who had arrived on India’s west coast from Iran during the 10th century CE, Sabavala could focus with deep empathy on the figures of the exile, the pilgrim, and the wanderer. He reached out, with equal empathy, to the experience of hard work and austere devotion: in his stylised manner, he memorialised the shepherd, the farmer, and the monk. And, as a creative intelligence who prized the possibility of transforming consciousness and experience through art, he would, on occasion, essay a self-portrait as a sorcerer, mage, or wizard.

Sabavala could also open his imagination up to presences from other dimensions or visitors from the future, who would land on the pebbled strands or agave-studded deserts of his paintings: apparitions, visitants, shamans, inhabitants of the worlds of myth, legend, and archetype. While the protagonists of ‘The Women’ III (1992) are more substantially part of an economy of labour, an ecology set at the edge between water and land, the protagonists of ‘The Seers’ II (1972) embody the more visionary and ethereal aspects of Sabavala’s figuration.

As we take our leave of this exhibition, I carry away with me a cherished memory of the artist in his studio: moving with unerring grace around that rectangular white room, alive with the smell of turpentine, freshly laid paint, and sunlight on canvas. I think of Sabavala as he would choose a brush or palette knife from a neatly arranged row of jars; as he would address his scale of colours, set out in rows like a musical score. And there would be the canvas, standing on the easel, the outlines of forms mapped across it in charcoal. Over the space of a few weeks, the canvas would breathe colour, acquire density, become instilled with memories and dreams, take flight into the sky of the imagination. As his viewers, we are privileged to have accompanied Jehangir Sabavala on some of these flights; he has left them to us as his legacy.

Text by Ranjit Hoskote