NEW WORK 1999 2019: DHRUVA MISTRY

December 05 - December 31 , 2019

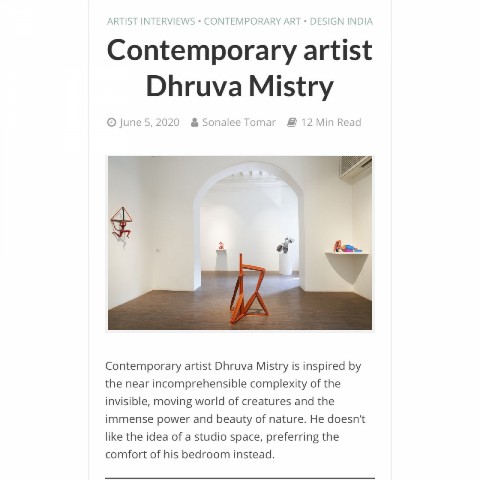

At first glance, the sculptures that make up Dhruva Mistry’s Six Seasons appear identical except for their colours, which are coded to the time of year they represent: yellow for spring, green for the rains, and so on. In each, a shape approximating a human figure seems to have been cut out of a steel plate and swung round by 90 degrees, staying attached at two points. On a closer look, the compositions belie their apparent simplicity. The solid form and negative space represent different genders and possess individually shaped limbs that aren’t a perfect match. Not only is there a contrast within each work, the pieces differ from one another in subtle ways. Mistry, in exploring what he collectively calls Spatial Diagrams, has evolved a gestural repertoire deployed in constantly varying combinations, while retaining the essential model of a swastika. The figures in Six Seasons evoke the cosmic relationship between purusha and prakriti while also playing out a human comedy about relations between the sexes.New Work: 1999 – 2019 consists entirely of sculptures in stainless steel, a material Mistry first used in 1995 to craft a version of a three-legged chair that stood in what was then his home in England. His depiction of chairs, and the human presence implied by them, led to the series titled ALoC or Actual Line of Control, four works from which are represented in the show. The chairs of ALoC resemble pulpits or thrones, sometimes containing sceptre-like diagonals crowned with spheres, relating to temporal power and the idea of control. They have evolved into architectonic configurations, cathedrals but also cages, dwellings of rulers and those they subjugate.

While ALoC and Seasons are tightly knit series, there is a looser grouping that can be discerned in the display, of torsos and seated and reclining women. These delicately balanced compositions prove surprisingly varied as we walk around each of them. Their creation required precise detailing in AutoCAD, the programme Mistry has used to design all his recent output. Should one of the measurements be off by as little as a millimetre at the point of contact between two laser-cut sheets, the error will be magnified hugely by the end of its length, the way pushing on a lever causes ever greater movement as one gets further from the fulcrum. Creating complex figures that are nevertheless stable is a technical challenge that the artist has overcome with each new figure in the group.

He has painted two of the reclining bodies by hand, a departure from the bare metal or evenly spray-painted surfaces he has employed for a decade. This represents a new phase in his recovery from a stroke, and is a testament to his will power and commitment to creation. At the formal level, these pieces recall a history stretching from the 16th through the 20th century, taking in Italian renaissance nudes, the paintings of Ravi Varma, the Futurist experiments of Umberto Boccioni, the late, angular sculptures of Henri Matisse and the undulating female figures of Henry Moore. While these influences can be guessed at or deduced, the works make no direct art historical citation, and viewers might bring an entirely different set of references to bear on them. Their impact depends less on such connections than on the exhilaration of mind sparked by an encounter with what seems familiar but abounds with unanticipated perspectives.

The three groupings – female figures, ALoC and Six Seasons – make up the core of the exhibition, and are complemented by individual or paired works from other series the artist has conceived. Two bird-women, Little B and Little B in Yellow, draw on the myth of kinnaris, while HanuMan: A Spatial Metaphor, is inspired by the famous legend of Rama’s greatest devotee transporting the entire mountain of Dronagiri to resuscitate the fallen Lakshman. The man-monkey and pyramid-mountain embody the combination of figuration and abstraction that runs through the show.

Doodledom is at once playful and ominous, an octopus-like creature that stands on tentacles, legs and gun-shaped limbs. It is the sole direct incursion of violent strife into the show. Mistry is deeply concerned with politics in his personal capacity, but has not engaged with it through his art aside from sidelong allusions like the title Actual Line of Control. He has incorporated the swastika without reference to Nazi history, and Hanuman without any association with Hindutva, working independently of the current preoccupation with politics just as he ignored the phase of post-modern irony and referentiality that was prominent not long ago. His prime concern remains a fundamentally modernist commitment to formal inquiry and to the potential of three-dimensionality, and New Work: 1999 – 2019 demonstrates the vitality of that single-minded vision.