August 10 - September 18 , 2023

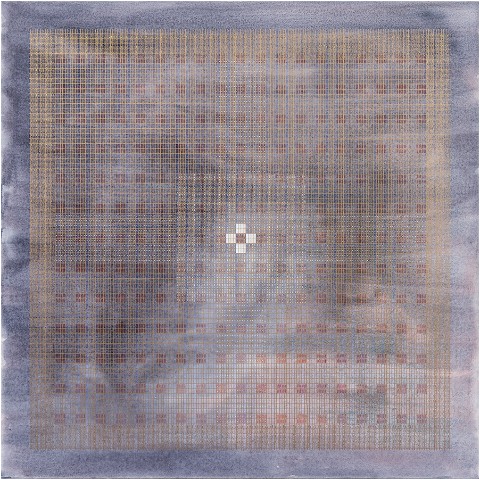

The line moves from a dot to a grid. The grid expands into patterns

of structure that pause, create and slowly disperse into a formlessness that

celebrates control and freedom of the breath, the mind, and the space in

between. All of this takes place in the now, in the present, in the contemporary.

Time moves in the form of constant nowness in Trishla Jain’s work. The two

series, ‘Yantra’ and ‘Tantra’, which expand Jain’s first solo exhibition at

Akara Contemporary, may initially stand starkly apart from each other but, on

slow immersion through time spent with each painting, the dots and dashes

configure themselves differently across canvases to create new compositions.

These configurations resonate with the present, which arises from a mindfulness

associated with discovering the expanse of space between the breath and the

mind that exists within each of us.

A self-taught artist, Jain turned to the canvas at a very young age.

Growing up in a large joint family in India, she spent her childhood learning

about rituals and life cycles from elders in the house. Her yearning to

understand the essence of life, its purpose, and fragility began at the age of

eight, the same time as her first canvas painting. Jain’s early journey with

spirituality led her to read religious scriptures and observe weeks of silence steeped

in meditation. Years of this practice led her to delve into the extreme

directions towards which the human mind oscillates. Fascinated by the mind’s

possibility to be completely distracted, gathered, dissatisfied, scattered,

centred, or contented, the artist in Jain set out to explore this on canvas.

She describes painting and meditation as two dancers who have been together in

her life since a very young age.

Conversant with

painting and its form, Jain turned away from formal training at art school and

instead chose to study English Literature and Anthropology while continuing to

work through the medium of paint, developing unique methods. Her early conversations with canvas sought joy, peace, and

other emotions that were more a portrayal of an outside desire rather than a

reflection of herself. Over time, as her spirituality grew, she retreated into

a more forgiving way of painting that involved surrender, mindfulness, and

acceptance. As a professional artist now, Jain also considers the act of

painting a form of meditation. In her studio in Palo Alto, she seamlessly

transitions and alternates between seated meditation (stillness) and active

meditation (painting). Greatly influenced by the minimalism in the American

abstract artist, Agnes Martin’s paintings, Jain works towards arriving at the

essence rather than the figure of what she wants to depict. Through a mindfulness

of breathing with relation to time and space her work starts to become less, and

hence begins to grow.

The mind, breath,

and space are three important anchors to understanding and experiencing Jain’s

work. The state of samadhi, the human mind’s experience of undisturbed

peace, structured over five stages acts as a key entry point into her paintings.

Vitakka (initial application of the awareness of breath) translates into

horizontal lines, Vicara (sustained application of the awareness of

breath) becomes vertical lines, Vitakka-vicara or piti

(spontaneous arising of rapture and joy) lies at the intersection of lines, Sukha

(easeful contentment) rests on the dots, and Ekaggata (gathered and

unified mind) is a unison of all the above elements to complete and expand

Jain’s paintings. By incorporating a painted attribution of choreographed dots

and lines, the artist maintains her core practice while also opening her work

to viewers receptive to an interplay of time, control, and its loss.

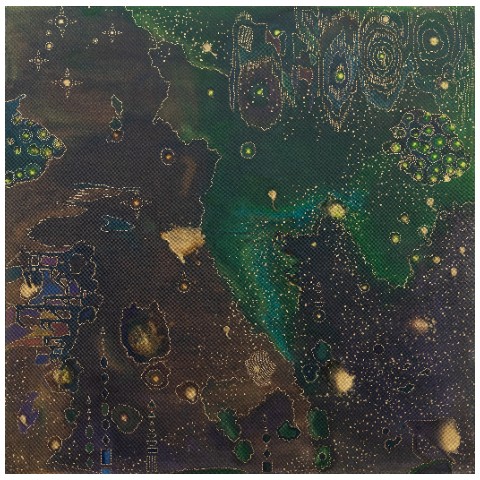

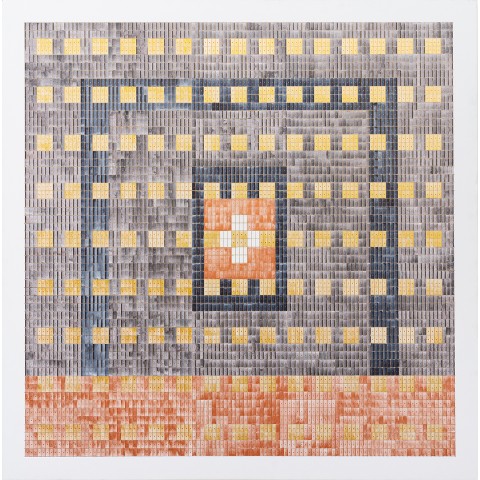

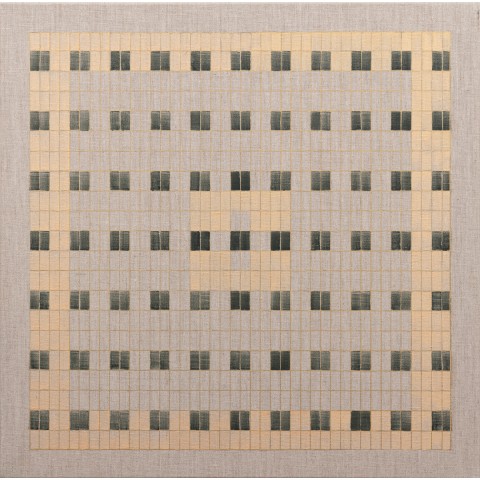

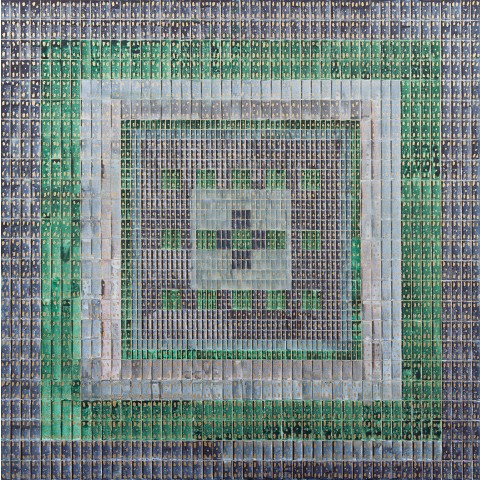

‘Yantra’ (2020 – ongoing) and ‘Tantra’ (2021 – ongoing), Jain’s most

recent series of paintings, resemble dualities and opposing parts that exist

within all of us. She refers to them as ‘yin and yang, the male and female’,

which allow her to bring herself to the canvas, not in fragments but as a

whole. Though ‘Yantra’ started a year before ‘Tantra’, today the artist works

parallelly on canvases from both series in her studio. On closer observation,

viewers will notice extremely structured elements such as the grid and patterns

from ‘Yantra’ in the ‘Tantra’ series and vice versa. While ‘Yantra’ deals with

a systematic progression of the focused, logical, and structured mind that

helps understand Jain’s layers of entering the state of samadhi;

‘Tantra’ takes on the same mind in its unleashed, challenged, and boundless

form, flowing free. Yet, the breath returns to centre both series of paintings.

Every line, dot

and grid in ‘Yantra’ is representative of the inhalation and exhalation of the

artist’s breath. The mindfulness of breathing that presents itself with a

beginning and an end in ‘Yantra’ resembles the concentrated form of the mind

where everything is in order to appear with clarity. The centre is clearly

determined within the structure until, with a slow release, the breath is let

go in ‘Tantra’. On losing sight of the constructed geometric order that

contains measured understanding, it is first chaos that takes over the mind.

However, the moment acceptance reigns over the abstraction of form, freedom is

instantly harnessed with complete surrender. By adjusting to the openness of

‘Tantra’ and observing it with time, the breath gradually returns to point out

symmetry and order even in its chaos. The tiny dashes of brushstrokes are

measured lines of breath and every now and then one can spot a constellation

forming only to disperse back into the flow of another order.

At a time when everything in our world seems driven and controlled

by technology, Jain’s works invoke a sense of surrender grounded in trust that

comes with letting go of control to accept freedom. There is sustained

mindfulness in this achievement from observing oneself through the breath and

mind in the present moment, in the ‘Nowness in Time’. With this alignment of

the mind and breath, there is a very conscious space that arises within the body

of work and the human body. For a form to be defined it requires space. It is

only when there is distance that one begins to observe patterns, grids, and

structures. On coming too close, the detail takes over but then pushes the

viewer back to create a space that allows one to be absorbed into the

painting’s entirety. It is in this act of emptying that we are nourished to the

brim with a contemplative energy and light which brings with it contentment, peace

and harmony. In ‘Tantra’ particularly, the mediums of gold oil paint with

watercolour repel each other in dramatic ways to create patterns of space on

the canvas that connect back to a positive-negative force akin to two magnets

that work to intensely push away only to align with each other by embracing

opposites and differences. By accepting this space there is suddenly an

articulation of a self-reflective silence that comes to rest and seeks to stay

in a cultivated reception of the truth, of the present, of the miraculous now.

This is not a silence of fear, but rather a conquering silence of peace, of acceptance,

and of letting go that allows for a flow of thought and mindfulness in a moment

that is beyond the past and short of the future; it is the moment of now that

centres the viewer back into a universal present in the nowness of time.

Veeranganakumari

Solanki