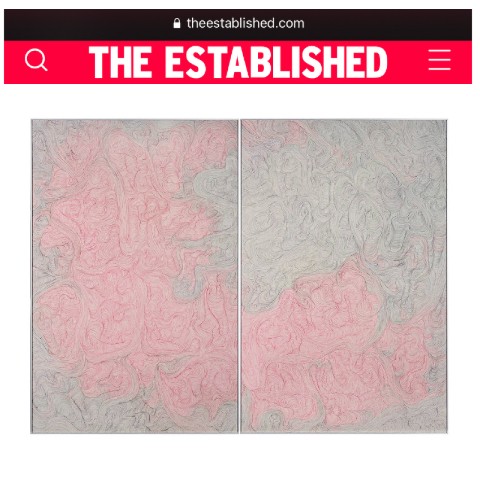

PORTRAITS OF INTIMACY - SATHI GUIN

February 10 - March 26 , 2022

I wonder what a pattern thinks, as lines and gaps infiltrate a surface. I wander in a pattern with my eyes walking the contours of shades and shadows, and patterns are cast as we move along its landscape. Textures traverse before forms take shape. I share these ruminations as I witness and share time with the works of Sathi Guin, the Vadodara-based artist. Guin talks about the hours she spends on her works as they emerge and take shape, line after line, and a landscape of thoughts emerge from the canvas – the thoughts are hidden, embedded, shying maybe behind the lines – you witness the lines and marks that fill the canvas. You watch the lines and dots, the patterns and textures – you are the watcher, you are looking for stories, you see textures, and you note patterns.

A texture is a landscape of incidents, marks, and traces, that have emerged over time; textures may let you perceive visual depth and touch, but what textures most importantly do is they mark and reflect on Time. Woven or drawn, as eyes and hands work with a surface to mark or carve a pattern – a configurations of lines, and spaces, motifs and colours appears – and the pattern grows only deeper with more lines over more Time. The doer, the worker, the artist, the craftsperson converts Time into labour, converts patience and precision into a pattern, and they use Time, to draw out visual encounters using lines and dots, producing motifs, while recalling memories – they embed and nurture the narrative within the abstract.

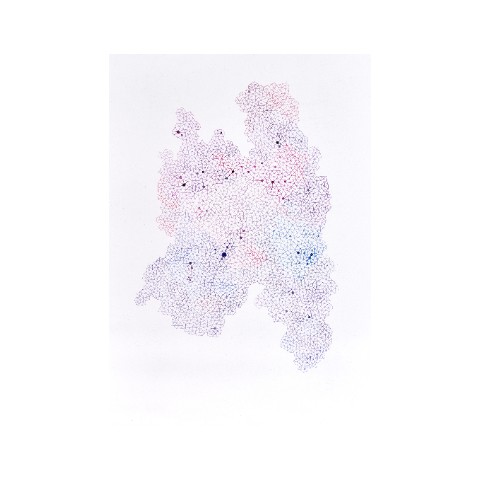

Are these portraits? Are these landscapes? Are they just about a set of visual occupations on a surface, now demanding depths of viewing? As you see these vast constellations of travelling lines, many landscapes of the mind emerge, many landscapes from the world around us emerge, from nature and the cosmos. But something tells you these images, these drawings, are maybe actually pictures – they are projections of the self, the artist-self to begin with, and now maybe your-self. The lines become personal, in their drawn fragility, as if the jottings in a diary, they speak of an intimacy between the drawer and the drawn, between the line and the surface, between line and line, between lines and the constellations they are shaping through your eyes, between the clusters of marks on a canvas and your eyes. These are then, in the bodily engagement of the artist’s hand and time with the drawing, her portraits of the self. The self is not an image, but the self is labour over time, and time as the space of being one’s own, with one’s self.

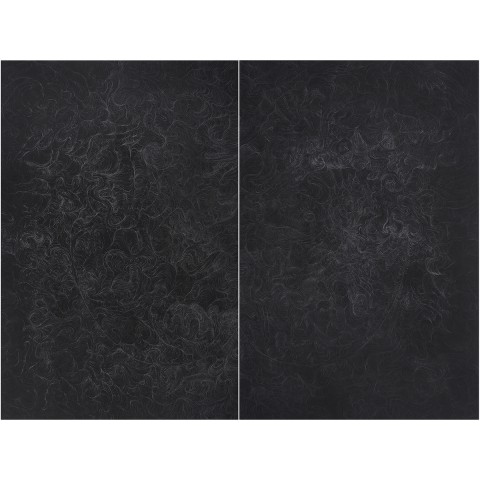

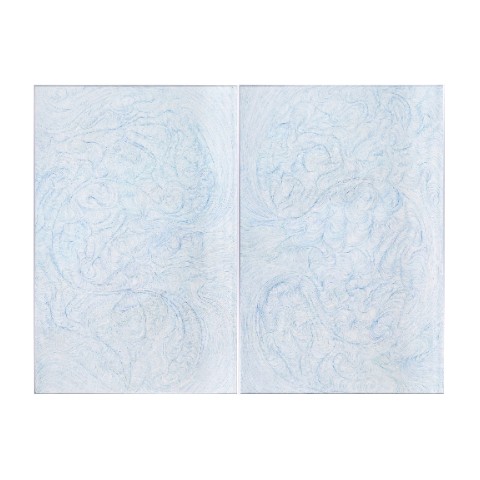

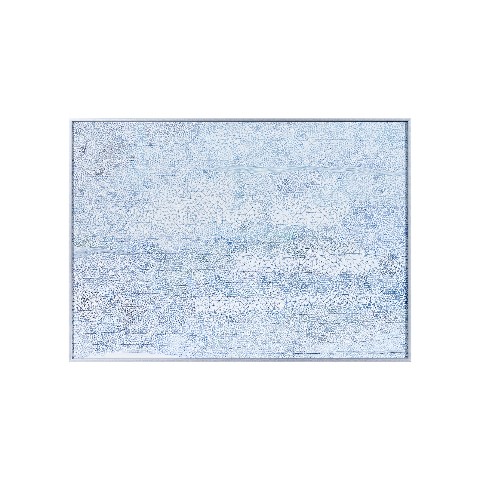

In the work of Sathi Guin a purposeful elaboration of time at hand is evident in the way her intellectual and bodily self gets engrossed producing textures and patterns – where from the apparent nothing comes something, and abstraction and elementary marks produce landscapes of clouds, forests, waves, and dunes. Your body, dear viewer, is invited to continue her work with your eyes, and see inside and beyond as you will wonder and wander, moving closer and farther from the work, trying to search, find, something. When you see the abstract map of lines and spaces, dots and sequences, you wish to see the routes and shapes of mountains you imagine are hidden there, and when you move away or to your side and see that cloud burst or canopies of galactic occurrences, and seem to recognize what you see you soon feel the urge to leave the uncertainty of that anticipated narrative and move back into the abstraction ostensibly identifiable as lines and spots. You wish to see, but the texture is no more simply the touch of a surface, it is in fact the intimacy of a Time spent with the skin of a form taking shape; the presence of an artist has created a sense of time and lines, spaces and moments; they are intimate, and draw you in as you see, yet eluding you just then, as well. The artist’s will to share intimacy, is your fear to be judged as a voyeur. The artist and viewer in these works by Guin are constantly in close touch by this game of allowance of viewing and the fear to see too much!

Guin in her earlier works used her thumb to cover surfaces with marks, forms, and impressions producing directly the body, the physical self, on the canvas. The self is present directly on the canvas as impressions, and the art and artist are intertwined in their presence there. These impressions often accommodated, or were enmeshed with images and icons such as a working or retired body, a kerosene stove cooking, a forest shedding leaves; the anxiety of stories within these landscapes of thumb impressions was presented through the iconic-format. Deep in colour and expressive vibrantly these early works indicated the struggle of the artists to represent and negotiate the space of the canvas as well as the space of the self. The artist as a woman, the artist with a childhood, the artist with memories of objects from her childhood, and the warmth of domesticity, as well as the demands of domesticity – these complexities of the mind, the memory, and the everyday history is what the artists is negotiating, and struggling to resolve. The canvas, the thumb, the colours, the iconic-aniconic, are her mediums to think through. Time and space as they exist in our everyday lives, or a woman’s life, or a child’s life, or an artist’s life, or a mother’s life – become nuanced and detailed as against broader abstractions of Identity and the world, the social or the familial. Her current works in their resolution of smoother lines and well-composed constellations do not iron out the anxieties, but fold them well in the deep layers of a geography of the mind that these landscapes and portraits of intimacy hide, and sparingly reveal.

As a child for Guin the process of doodling was an activity unto itself, it was not the outcome of that exercise but that very exercise that occupied her; engrossed in drawing was a way to carve space of one’s own, amidst and against the hullabaloo of a family home. In many ways Guin’s engagement with doodling, and drawings, that involves a sense of repetition, conducting an activity that involves processes of repetition, rhythms of task-cycles, reminds one of other such activities such as knitting or embroidery, or for that matter even taking regular long-walks. Activities that are self-contained in their composition, are recurring in actions and tasks, are also immersive and in cases meditative, allow the doer ‘a room of one’s own’ amidst the strains of everyday objects and relationships, and pressures of being. The drawer, the doodler, the walker, carve out a space and stretch time for themselves while carefully shaping their time, and thoughts, or ruminations in the weaves and intensities of lines, or woolen threads, or pathways. Guins works are part of this expedition to search for space, and occupy one’s time for one’s self.

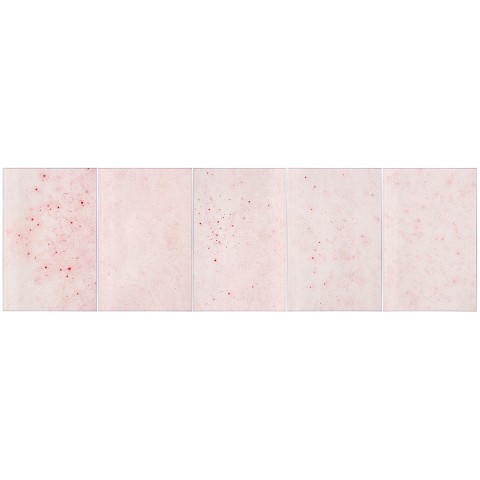

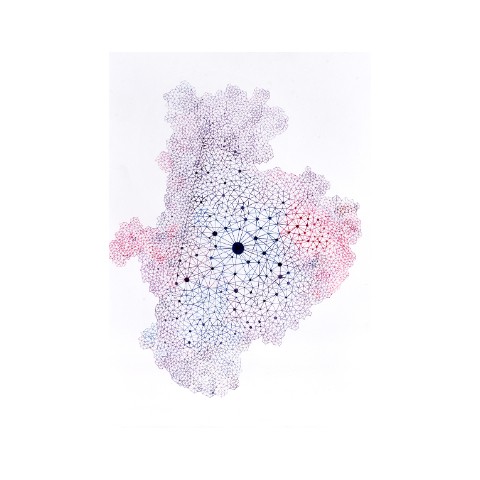

Each work in the current body is unique although it clearly shares strong similarities in the visual outcomes, its form and language. While in some cases, the lines take longer commitments, running over lengths, shaping stronger curves into depth-folds, in others the lines are synapses like electric sparks, short and snappy connecting into a network that appears and disappears. There are those that are synoptic and sit within a single cone of frame – readable as a country’s map, or a small watercolour landscape, or even a large composition of smaller, miniature drawings separated form a jigsaw puzzle. There are those you walk along like with a wall mural, and some you love to see as a framed, and precise image, even if amoebic or abstract. As much as the use of very basic elements repeats one work after another, in their manifestations as frames and sizes, they create broader worlds of containment or apparent continuity beyond the frames; do these canvases capture a frame in a larger occurrence, or are they the complete figure of being within?

The aesthetics of Guin’s works bring to us a delicate beauty, and one wonders what is the home of that delicate beauty? Is it the skill of the hands? Is it the command over colour? Is it the sense of composition and frame? Or is it the journey the eye searches for amidst these lines, colours, and compositions – it is a map at times, a landscape peeks through in some, or is that embroidery of red spots and lines of some fine craftsmanship or the memory of spattered blood; is it the tissues of worn-out skin, or the residue of fresh birth. The delicate beauty is in the delicate balance between the sensibilities of seeing, the witnessing of drawn labour and time, and the recall of memories and images from an archaeology of our own histories.

Guin’s work is in suspension between form and meaning, between labour and memory, between search and self; and we dear viewers somewhere are drawn into experiencing that suspension – that in-between moment of knowing and not, of seeing the familiar yet wondering about the unsaid, of being drawn into intimacies you wish you could see, but as soon as you see you feel guilty of being the voyeur. The beauty is delicate, and it is terrible; much like intimacy is delicate, beautiful, but also terrible, and maybe lonely.

-Kaiwan Mehta