THE RETURN OF THE BAROQUE: JONATHAN TRAYTE & REBECCA SHARP

November 09 - December 16 , 2023

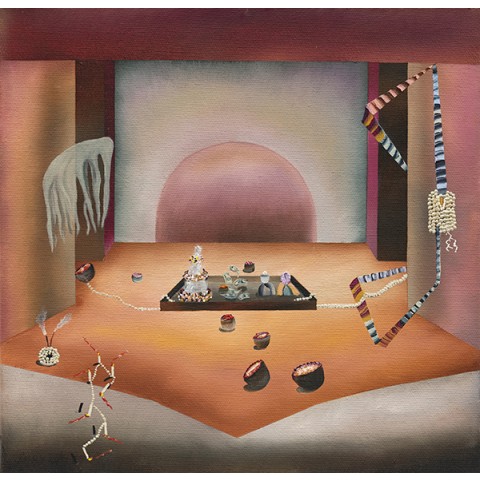

At first glance, Rebecca Sharp

and Jonathan Trayte might seem to have little in common. A painter, Sharp (born

1976) emerges from an American-Brazilian background. She is closely engaged

with the shamanic and carnivalesque energies of Brazil’s popular culture. She

works, also, through an ongoing critical conversation with the women artists of

the 20th-century avant-gardes and their incandescent legacies of

experiment in life and art, which had until recently been under-regarded. A

sculptor, Trayte (born 1980) was born in Huddersfield in the north of England

and spent time in South Africa as a child. He has worked as a sous chef at a

farmers’ market and restaurant, and is preoccupied with the forms, colours and

circulations of a consumption-oriented mass culture that has come to be defined

largely by supermarkets, restaurants and cafés. And yet, marvellously, even

magically, their oeuvres come together in a generative space of dialogue.

Sharp, whose paintings draw as

much on the vibrant folk-Catholicism of South America as on the surrealism of

Leonora Carrington, invites us to open ourselves to the plural dimensions of

space, time and identity that we inhabit, and which we do not always

acknowledge. Trayte, whose sculptures gesture as much towards Claes Oldenburg

as towards Ettore Sottsass, urges us to blur the genre distinctions we make

between materials and experiences, underlines the similarity between sugar and

glass, flour and plaster. What strikes me most compellingly is that both these

artists return – by routes that are quite distinct and through emphases that do

not coincide – to the legacy of the Baroque in all its grand extravagance. Both

Sharp and Trayte reclaim the special gifts of the Baroque: its self-aware and

astute theatricality, which at its best was not an escape into fantasy but,

rather, a sublime enlargement of the alternatives to a constrained normality;

and its capacity for defying the proprieties and exceeding the limits of

medium, spatial context and intended audience.

*

Sharp’s paintings act as zero-gravity spaces or

miniature proscenium theatres in which figures, elements and signals align themselves

into enigmatic constellations. In these oneiric scenarios – richly inspired and

nourished by Brazil’s pre-Columbian and Afro-Brazilian cultures, yet also

informed by the artist’s transhistorical kinship with Yves Tanguy and Frida

Kahlo – bejewelled fruits and crystalline geodes float alongside totem poles

and talismans, while guardian figures

conduct rites of transfiguration. Are they spirit guides waving wands, interstellar

visitors powered by light beams, phantoms, or Tantric guardians of deep psychic

realms? Sharp earned a master’s degree in Buddhist philosophy and is a questor

who cherishes viscerally transformative liminal experiences. Accordingly, her

paintings can come across as visual anthologies of hymns, anthems and

incantations, grimoires that spell out vital reserves of hope, resistance and

resurrection. In one of them, we encounter a banner blazoned with the title of

a Cynthia Luz song, “Eu nãu sou daqui”:

I’m not from here.

We sense the thrum of the

carnival in these works, with its entwined currents of passion and death, its

simultaneous unfolding of lives and afterlives, its choreography of ecstasy and

risk. This is not to romanticise or exoticise Brazil. As a gay person, Sharp is

painfully aware of Brazil’s contradictions. On the one hand, its gloriously

kaleidoscopic mix of Native, African and European cultures has given birth to a

surging creative freedom and an organic cosmopolitanism. On the other, the

country suffered decades of military dictatorship supported by the

arch-conservative sections of society; racism, transphobia and implacable

hostility towards the queer community have long been endemic features of Brazilian

collective life.

Shuttling between vistas of

extinction and the palpability of detail, mythic frameworks premised on

infinity and the clock time of history that is predicated on finitude, Sharp regards

herself as bearing the responsibility of the witness who can stand apart from a

human-centric narrative, and testify to processes of creation, destruction and

healing that involve all beings. She finds herself reminded of a teaching from

the Mahayana Prajnaparamita Sutras:

“Emptiness is form; form is emptiness.”

*

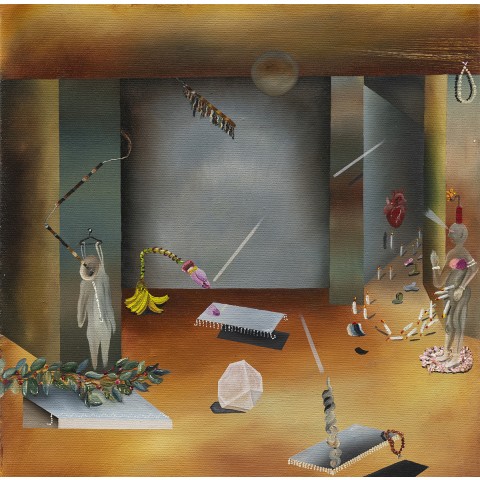

Trayte’s sculptures occupy a

shifting domain between toy, vitrine artefact, popular votive and commercial

fetish. They remind us of an East Asian-style display of ceramic or plastic

facsimiles of food laid out as a visual menu, with the intention of assisting

tourists across differences of language and culture. In Trayte’s handling, it

is vividly transformed into a marketplace iconography that can be fetishised

upward through labelling and branding. These sculptural provocations address,

with stylish vigour, a suite of themes that fascinated the pioneers of Pop Art:

food, leisure, the life of the street, advertising imagery, the effervescence

of the everyday. Trayte’s experiences in the domain of the culinary arts appear

to have informed his work as a visual artist. As we savour the felicity with

which he conceives, composes and assembles his sculptures, we sense, at work,

an expertise in combining flavours and sensations, in plating and presenting an

offering that appeals to several senses at once.

Trayte revels in the use of materials

culled from the everyday life of global capital: vinyl, aluminium foam, steel,

fabric, concrete. His forms direct us towards the temporalities of germination

and fruiting, fermentation and curing, boiling and refrigerating. Even as they

celebrate the vital pleasures of the table, these objects suggest that we pause

in our consumerist tracks and look more dispassionately behind our lavish

surfaces, our insatiably Rabelaisian appetites. In a move at once tender and

whimsical, Trayte’s sculptures also achieve a symbolic life of their own,

independently of these associations, as objects that seem part-cybernetic and

part-horticultural, seemingly awaiting a future in which they can properly

fulfil their destiny. This realisation may lead some of us to stand back and

look again, and look more closely, at his work.

Take away the insistent presence

of colour, as a thought experiment, and we may find that a number of Trayte’s

sculptures have far more in common with certain stand-alone modernist works in

three dimensions, which occupy a midground between maquette and monument,

astoundingly managing to combine the fragility of the former with the

confidence of the latter. Importantly, these works encourage an expansiveness

of association while retaining a self-possessed formal integrity. This would be

the point at which to recall that, as a child, he had lived close to the

Yorkshire Sculpture Park in West Bretton, Wakefield – and played among the

Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth sculptures there.

Despite their very different

starting points, Rebecca Sharp and Jonathan Trayte offer us surprising visions

of contemporary global experience in all its interwoven and multi-layered

complexity. They respond to impulses within the avant-garde traditions of 20th-century

art, not by merely treating these as quotations, but by translating the

art-historical archive into living, artisanal material that can be played with

and reconfigured. At the same time, they are also robustly and intimately

responsive to the public culture and popular traditions of the societies in

which they grew up. Significantly, each of these artists brings their larger

cultural explorations back to bear on the singular painting and sculpture,

which are not dispersed or expanded into larger assemblages or installations. Together,

Sharp and Trayte urge us to become active and attentive pilgrims again, rather

than indolent passengers riding the algorithmic cascades of narcissism and

complacency.

*

-Ranjit

Hoskote

Images

Installation