YES, BLUE! BUT WHICH BLUE - UTKARSH MAKWANA

January 12 - February 25 , 2023

Utkarsh

Makwana gives water-based paints an elastic quality, an oil-like pliability. He

mixes dry powder pigments mixed with gum arabic, casine, or gouache binder.

Sometimes, he will dabble in acrylic. He works with paper, but at an enormous,

immersive scale. Makwana’s paintings are expanded, and they take on a

structural quality: it is as though you enter his compositions, and there are

certain internal manipulations done by the artist to animate our viewing

experience. He often begins a work by first dividing up the painterly plane

into sections, which are informed by individual geometric equations. He works

with orbs, cubes, octagons, horizontal lines, many-sided dimensional objects,

and more – each of which come together or individually in fractal alignments

that variate across the paintings. Through this, the artist creates several

levels by which to enter the work, and Makwana’s spatial configurations vary

the complexity, density, and scale of the works.

The

artist often begins with structure, an architectural constitution. This

determines how we view the work: how our eyes travel along lines and grids;

what points of the canvas we are drawn to by a rhythmic logic; which details

appear as though magnified sheerly by their relationship to pattern and volume.

It’s a discrete, yet animated choreography, and Makwana devises this with

intention. He is inherently inspired by the geometries of nature, of how even

the most chaotic organism is determined through its relationship to equations.

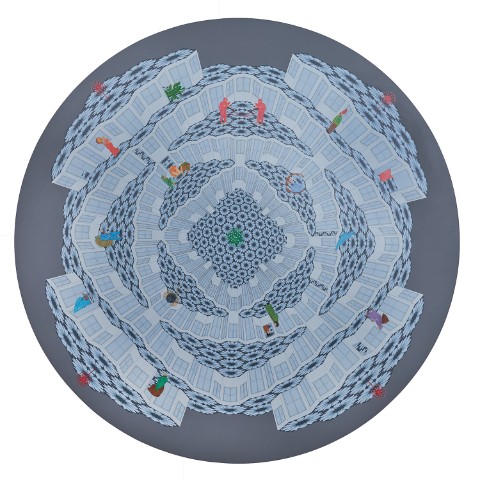

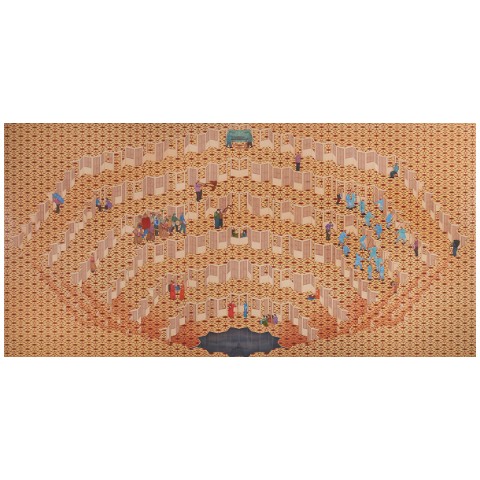

In Tales from a Valley, for instance, we have seven storeys of decked

and staggered planes, each densely drawn out with circular, self-similar

geometric markings that appear as though endlessly forming their own variegations

– one arc is drawn from the other, one angle informs the next. It is an

entropic upturn of form. At the bottom of Tales from a Valley, we see

the ground break open as though into a void, which upon a closer look seems to

be the inverse of the scene that precedes it – a still body of water perhaps,

or even a parallel timeline. The pictorial plane is cleaved by Makwana’s

delivery of perspective: a chasm is created which makes the painting seem as

though it is able to unfold infinitely, as though it exists even further than what

we are able to visibly see.

While

at art school, Makwana was deeply interested in the Mughal miniatures, and these

have informed his handling of the work. Small figures populate the scenes, as

do specific tableaus of action and narrative. In Tales there are several

sets of musicians, troupes that travel together in a pack, some in special

masks, as though filling up a street during the time of a festival; a pair of

percussionists seated in the corner of a door frame, perhaps exchanging notes

about their tablas; a pair of brass players, instruments outstretched before

them, with long lead pipes and large bells; siblings, each on one side of a

corner, a single window open on either side, tucked into bed, with matching

forest-green quilts. At university, Makwana was often made to do a strictly

formal exercise in building perspective: students were asked to render the same

object or scene over and over again, each time from a different vantage. It was

an act of finding new angles by which to approach the same subject, both

literally and conceptually, as the act of shifting viewpoints has the potential

to produce nearly infinite differentials. It is almost the undoing of the

Kantian Thing in Itself – where objects exist outside of our capacity to

perceive them, as material, and as pure form – here it is an exercise in a

continuous kind of perception, a referential subjectivity and an outpouring of

possibilities. Where objects, patterns, structures, angles and topographies

cannot physically exist without the subjective mechanism by which we perceive

and understand them. Makwana’s material for this inquiry is purely geometric –

he carries forward this classroom exercise by – without interruption –

painstakingly returning to certain equations in splitting up form and line. As

a result of this almost obsessive inquiry, Makwana is able to create these

stunningly elaborate architectures that we may inhabit merely through the act

of looking at them.

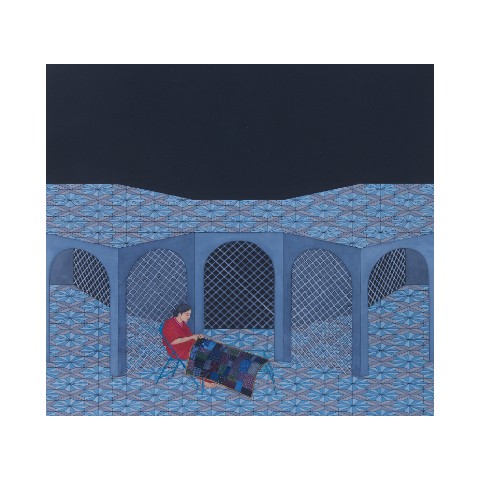

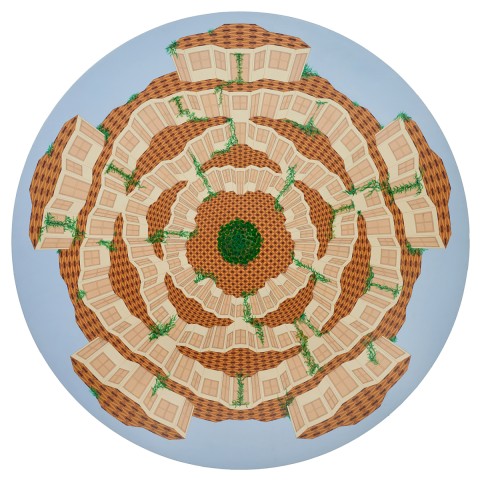

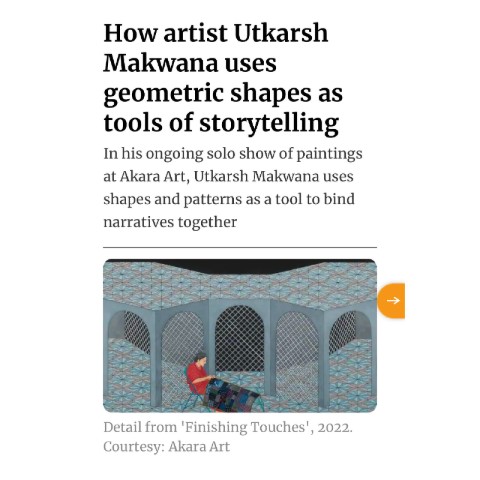

In Finishing

Touches there is only a single figure at the center of the frame, an older

woman, her hair tied into a neat, greying bun, bowed over a patchwork blanket –

indeed, applying the eponymous ‘finishing touch’ – she has a fine needle

clutched between her fingers and she is bringing her work to a close by

finessing its thin, delicate border. The blanket – or perhaps it is a rug, or a

wall ornament made of fabric – is comprised of several swatches of cloth that

themselves vary in style and colour. Each is vivid and individually characterised:

chequered, dotted, scalloped, or inundated by softly drawn waves. Here, Makwana

introduces the fabric as yet another carrier of geometry and line, and this

material floats over a pale blue floor carrying a cut-open design at whose

technological centre is a star-shaped repetition. Finishing Touches is

otherwise overwhelmed by this delicate, animated tiling, and characteristically

broken into levels by concertina arches – carrying a softly painted-in grill-work

reminiscent of the artist’s ancestral home in Ratlam, in the north-western Malwa region of

Madhya Pradesh – which unfold over the horizontal. This zig-zagging architecture once

again splits the plane of the work, adding depth, and structural complexity.

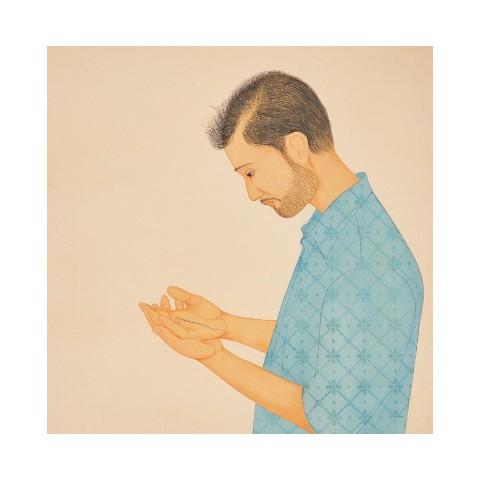

Fabric,

especially patchworked fabric, has a special significance to Makwana. He was

born to a family of tailors and fabric experts who have a shop in Ratlam.

Excess fabric would be brought home by the family, and the artist’s grandmother

would often compose large rugs with these pieces big and small. Makwana

remembers a time before interlock stitching techniques – mechanised by

automatic sewing machines – where dexterous hands would painstakingly pass

finely wrung overedge stitches on the unfinished seams of fabrics that each

varied in pattern, texture, and weave. Makwana’s family home would often be

taken over by these collaged textiles, conjuring an excess of design and figure

that seems to have seeped into his imagination. While the artist doesn’t

specifically work with fabric, there is a kind of synergy between tailoring and

his style of refined, deliberate geometric structure-making. On Sundays, as a

child, Makwana would go sit at the shop and observe the discipline of line and

form, of how compositions can be devised from the flatness of textile, and

animated into three – or even poly – dimensions. This is what Makwana does with

paper, too, he takes a flat plane and adds layers of dimension to it, creating

cavities that viewers may pass into the threshold of, and thus be wrapped

within.

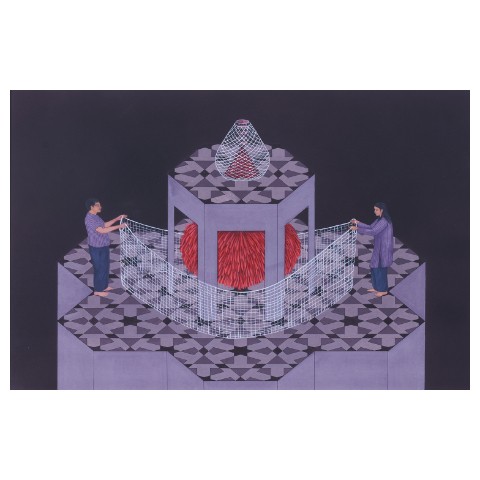

In Yes

Blue! but which blue two boy sit across from each other passing between

them two swathes of blue paper. A very large window opens out behind them –

it’s so large it may as well be a portal, a gateway between worlds – and it’s

filled with a speckled, starry, inky black sky. Along both lengths of the

window are a set of shelves, each cubby with an angular, polygonal,

many-dimensional shape carefully placed inside it. These are shapes sometimes

visible in Makwana’s other works, and the display here is as if a

deconstruction and purposeful exhibition of the assemblies that erstwhile

populate the artist’s works. Yes Blue! but which blue is composed

entirely in many shades of blue, to which the title nods. At the top right-hand

corner of the watercolour, a glimmering, single, shooting star streaks through

the sky, piercing the scene with an almost supernatural, and yet soft,

intensity. There is a

tendency that is inherently about discourse in this painting – an

illustration of a camaraderie, an exchange of opinions, a dialogue that traces

the subtle graduations and fineries of a single colour. It’s a powerful symbol

of the Platonic method: the purposeful examining and revising of a single,

seemingly small detail through the act of conversation, the deep examination of

one conception of truth as a manner by which to develop a more sophisticated

understanding of the same, and to arrive at fresh and new conclusions.

Makwana’s works force this kind of contemplation, one that is welcome, and also

generate an almost physical space in which we can have them.

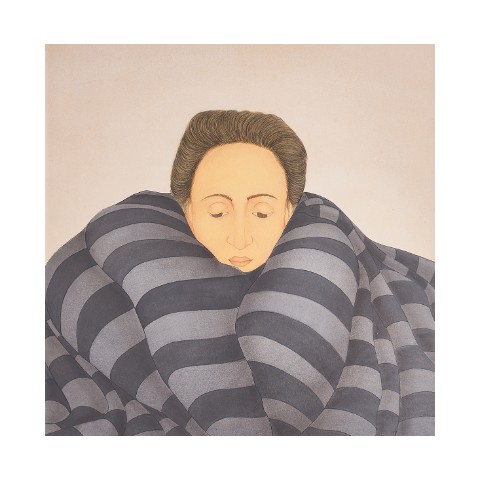

In the

body of work that comprises this show, Makwana is gravitating toward a specific

inquiry, one that foregrounds human experience, and emotions, in its

investigations. He is exploring storytelling methodologies alongside structural

ones, new vectors that are emboldening and moving through his practice. The

narratives that emerge on the painterly plane are derived from conversation,

from the anecdotes of the lives of his friendships and family members, from his

own personal history as well as the histories of entangled communities. He

deters from rendering anything too specific as at its heart a painting hopes to

create room for the viewer’s subjectivity. The works are both an invitation to

dialogue, as much as they are the architecture within which we can animate the

communication.