ZARINA 1980 - 2000: THE NOSTALGIC DECADES

June 08 - August 01 , 2023

Zarina

Hashmi came to art late in life and found her true voice even later. Born in a

home full of books rather than paintings in the north Indian city of Aligarh, she

graduated in mathematics, a discipline aligned with the geometry of her later

compositions. She married a diplomat and travelled the world with him,

discovering and studying woodblock printmaking in Bangkok, widening and honing

her skills in Tokyo, Paris and Bonn, learning paper making in Rajasthan, before

settling down by herself in a New York City loft that bore little resemblance

to the opulent homes she had previously occupied. Her itinerance is detailed in

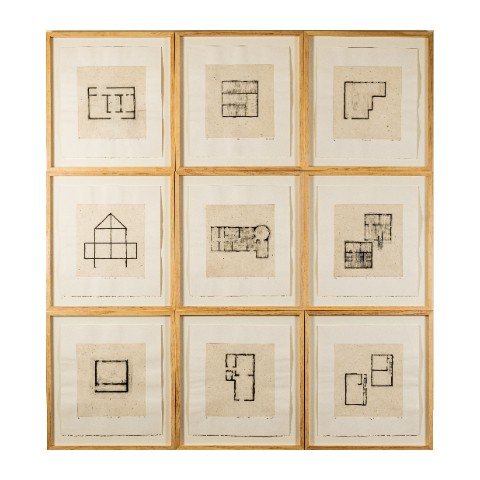

one of her first great series of prints: Homes

I Made: A Life in Nine Lines, a centerpiece of the present exhibition, which

was created in 1997 when the artist was 60 years old and at the peak of her

powers.

Zarina’s

work from the 1980s until the start of the new millennium was driven by nostalgia.

The word was coined by a Swiss doctor in the 17th century from the

Greek words ‘nostos’ meaning the return home, and ‘algos’ meaning pain. The

doctor used it to describe a severe, often debilitating homesickness felt by

Swiss mercenaries who had accepted military service far from their peaceable homeland.

In the twentieth century, literary and artistic nostalgia was sharpened by the

understanding that there was no home to go back to. The pace of change had

grown so rapid that emotional connections could no longer be recovered through

the act of return. This was certainly true for Zarina, many of whose family

members, including her sister Rani with whom she shared the deepest of bonds,

migrated to the newly formed state of Pakistan in the years following 1947. She

was beset by a feeling of being uprooted and adrift even as she fashioned a

successful life in New York City as a printmaker and member of the feminist

arts collective Heresies. Her homesickness, however, unlike that of the 17th

century Swiss mercenaries, was enabling rather than debilitating.

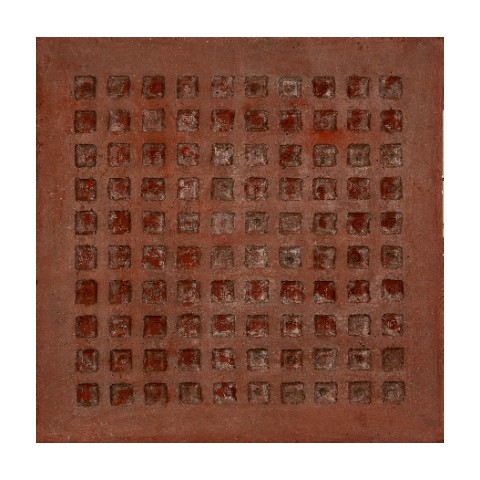

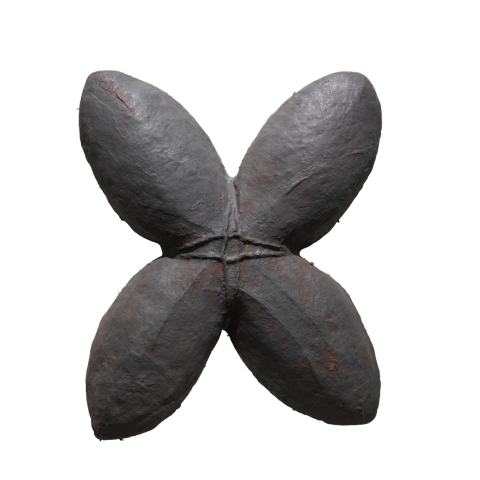

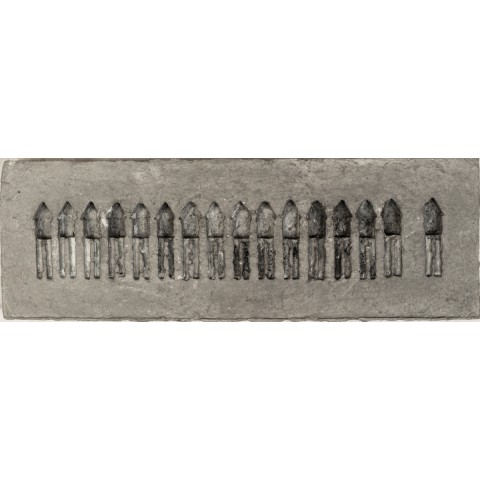

Her

breakthrough as an artist came when she began combining nostalgic memories with

her interest in architecture and attraction to spare form. In the 1980s, she

employed the unusual medium of cast paper to make a number of monochromatic

sculptures; one of a flower from a garden whose fragrance lingered in her mind;

another of a row of neo-Gothic arches, emblems of colonial cities; a third of a

grid that brought to mind the red sandstone of Fatehpur Sikri whose

architecture she loved, as also the jalis

of zenanas, perhaps the most fabulous of which are found in Mehrangarh Fort in

the state where she learned to make paper.

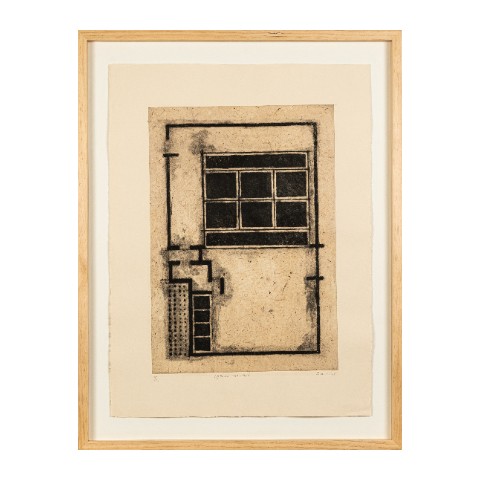

Through the

course of the succeeding decade, nostalgic references became more explicit,

permeating Zarina’s work in her field of technical expertise, printmaking. She

had since the 1970s placed herself within a tradition of minimalism that

included figures she admired like Kazimir Malevich and Carl Andre, creating

silkscreens with geometric black Tangram-like shapes and delicate

white-on-white embossed compositions. She now brought to that history of

minimalism an emotive, autobiographical dimension it had hitherto lacked, so

much so that the phrase ‘autobiographical minimalism’ would have felt

self-contradictory before Zarina’s prints of the 1990s.

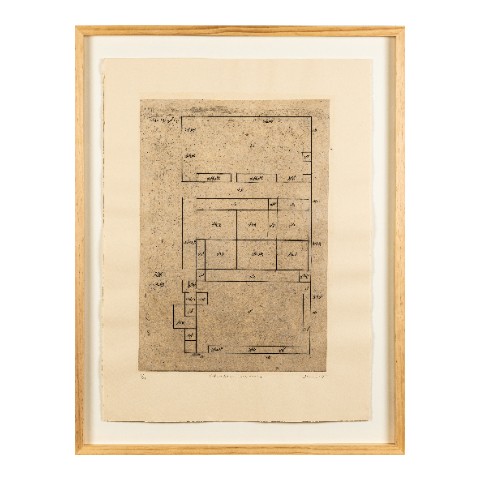

The

unlikely vehicles for her expressive nostalgia were floor plans: of her

father’s house in Aligarh and other dwellings she had inhabited around the

globe. Diagrammatic floor plans are among the most utilitarian of illustrations

but, in Zarina’s hands, with a few carefully crafted stains and smudges

disturbing their strict linearity and the addition of evocative titles, they became

carriers of profound emotion, effectively conveying her sense of loss,

displacement, and yearning.

The attacks

on the World Trade Centre in her adopted home city on September 11, 2001, and

the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that followed, altered the trajectory of her artistic

development. She delved into geopolitical and civilizational clashes involving

the Islamic world broadly defined, depicting aerial views of contested lands

and cities in conflict zones. At the root of these explorations lay the trauma

of Partition, symbolized by the Radcliffe line dividing India from Pakistan

which appeared more than once in her work in this period. While she did not

abandon intimate, personal narratives entirely, they ceased to dominate her

output.

Her work in

the last two decades of her life leading up to her death in 2020 was always

rigorous and consistently evolving. She had used gold ink occasionally in past

years and now regularly employed rich gold leaf in two and three dimensions,

not only for its visual qualities but for its associations with spiritual

purity in different religious traditions. These dazzling, joyous works serve as

a counterpoint to the tales of strife she had narrated in the wake of the 9/11

attack and to stark images of migration and forced exile she crafted in her

final years.

There is so

much to admire across Zarina Hashmi’s oeuvre that it would be unfair to pick

out one period as standing out from others. However, to my mind, if we restrict

ourselves to the sheer emotional impact produced in viewers, which is only one

among many potential vectors of analysis, the groundbreaking nostalgic works of

the 1990s represent the peak of her achievement.

-Text By Girish Shahane